Short History of Galicia

For Family History Researchers: Understanding Galicia’s Complex Past

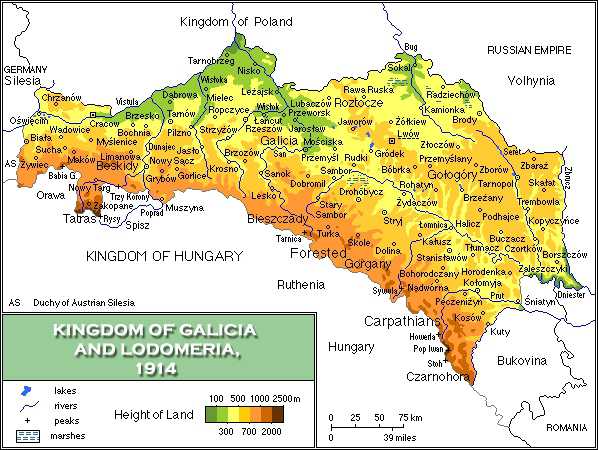

1. Galicia in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (1772–1918)

Galicia was created in 1772 after the first partition of Poland and became the northeastern province of the Habsburg (Austrian) Empire, with Lemberg (Polish: Lwów, German: Lemberg, Ukrainian: Львів) as its capital. The province included territory that is now in western Ukraine and southeastern Poland. Galicia was famous for its diversity. Poles mainly lived in the western part, Ruthenians (now called Ukrainians) in the east, and there were large communities of Jews in most towns. Armenians, Germans, Czechs, and other groups also lived here. By 1910, the population was about 45% Polish, 42% Ukrainian (Ruthenian), and 11% Jewish. Major cities included Lwów/Lviv, Stanisławów (now Ivano-Frankivsk), and Tarnopol (now Ternopil). The population practiced Roman Catholicism (mostly Poles), Greek Catholicism (Ukrainians/Ruthenians), Judaism, Armenian Christianity, and smaller Protestant and Orthodox faiths. After some strict early years, Galicia gained self-government in 1867. Local administration, schools, and the church kept detailed records—civil, church, and Jewish community archives from this period are especially valuable for genealogists. The late 19th century saw a rise in both Polish and Ukrainian cultural and national movements. Many people emigrated, especially to North America, because of poverty and overpopulation. The building of railways helped movement between towns and cities.2. After World War I: Polish Rule (1918–1939)

After the collapse of Austria-Hungary in 1918, Galicia was fought over by Poles and Ukrainians. The West Ukrainian People’s Republic was briefly declared in Lviv, but by 1919 Polish control was established. The Peace of Riga (1921) confirmed Eastern Galicia (with Lviv and most of the former province) as part of the Second Polish Republic. The interwar years brought both modernization and tension. Polish was the main language of government and public life; many Ukrainians felt marginalized, especially in education and administration. Despite these tensions, the region’s towns—like Lwów and Drohobych—remained vibrant, with active Polish, Ukrainian, and Jewish communities. Difficult economic conditions led to more emigration. For researchers: records from this period are often in Polish, but some Ukrainian and Yiddish documents also survive.3. World War II and the Holocaust (1939–1945)

The outbreak of WWII in 1939 again changed Galicia’s fate. The region was divided between Soviet and Nazi control: the Soviets took Eastern Galicia (1939–41), arresting and deporting many Poles, and closing religious institutions. In 1941, Nazi Germany invaded, and Galicia suffered greatly during the Holocaust. Jewish communities in Lwów, Stanisławów, and other towns were nearly destroyed in ghettos, camps, and mass executions. During this time, violence between ethnic groups also erupted, with tragic losses for both Poles and Ukrainians. In 1944, the Red Army regained control of Galicia for the Soviet Union.4. Postwar Galicia and Modern Ukraine (1945–Today)

After WWII, Galicia ceased to exist as an official region—most of it became part of Soviet Ukraine, while a western slice (including Przemyśl) stayed in Poland. Soviet authorities resettled most Poles from Galicia to western Poland, and relocated many Ukrainians from Poland into Ukraine. Lviv and other cities underwent industrialization; Greek Catholic churches were closed until the late 1980s. The Jewish population, decimated in the war, was not rebuilt. For genealogists: finding postwar records can be difficult due to population transfers and changing borders; prewar church, civil, and Jewish records remain crucial. Today, Galicia’s legacy survives in the architecture, cemeteries, and family memories of western Ukraine (Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Ternopil regions) and southeastern Poland. Most residents now identify as Ukrainian, but traces of Polish, Jewish, Armenian, and other communities are still present.Summary for Researchers

- Place Names: City and town names changed over time and are often listed in Polish, German, Ukrainian, or Yiddish, depending on the era and document type. If you’re searching for family roots in Galicia, check out our list of 100+ Cities & Towns of Historic Galicia—each with names in several languages. Also explore our Galician Genealogy Resources for church records, civil registers, and emigration databases.

- Diversity: Galicia was a true melting pot, with multiple languages, religions, and traditions including Poles, Ukrainians (Ruthenians), Jews, Armenians, and other groups.

- Records: Many valuable genealogical records survive, especially from the Austrian period. Later wars and border changes disrupted continuity, so some records may be missing or scattered.

- Migration: High rates of emigration (especially 1880–1914) mean many descendants now live abroad; overseas archives may hold family records.

Understanding these shifts is key for family history research in Galicia—helping you find records and understand the changing identities and stories of your ancestors.

Further Reading

- Galicia (Eastern Europe) – Wikipedia Learn about the history, culture, and geography of Galicia, a historic region once part of Austria-Hungary and divided today between western Ukraine and southeastern Poland. This article covers the region’s diverse heritage, changing borders, and the people who lived there.

- House of Habsburg – Britannica Read about the powerful House of Habsburg, the royal dynasty that ruled Austria-Hungary and many other European territories, including Galicia. The article explains the family’s influence, important rulers, and their role in European history.